Weathering the storm

By: Emily Harbison with contribution by Bill Rufenacht | Technical Specialists, Dairy Connection Inc.

Here at Dairy Connection, we feel fortunate to have built strong relationships with many hundreds of creameries across America over the last 20+ years. Every day during this crisis, members of our team connect with clients managing the myriad complexities and uncertainties arising from this extraordinary situation. Our goals at this time include ensuring that our clients have the ingredients they need, as well as the technical support unique to this situation.

One frequent topic of discussion recently has been how some creameries are seeking to adapt their products and/or their processes to accommodate the challenges presented by their specific circumstances. Shelf-life is often part of these conversations. Products with a one-day shelf life cannot weather the same storm of market changes as a product with a 50-day shelf life. Below we offer some technical information that may be of interest to those researching options pertaining to extending or shifting the shelf-life window of finished products.

This is an overview; we urge you to contact us directly with questions on this topic, as every situation is different.

Yogurt, Sour Cream & Fresh Cheeses

A fresh product should be…fresh!

Day One is peak quality, and it’s downhill from there. The purpose of this post is not to portray it any other way.

With the current state of affairs surrounding COVID-19, some processors are busier than ever while others’ sales and production have skidded to a standstill. Slower inventory turnover can lead to increased food waste, lost revenue, customer complaints and more. The following is intended to identify potential tools in your toolbox to increase flexibility as a food manufacturer.

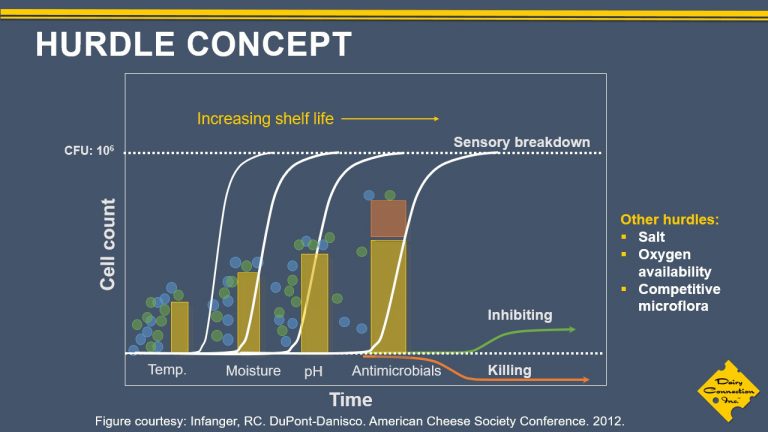

Shelf Life and Hurdle Technology

Foods can become spoiled from a multitude of causes, but the first-occurring defect is dubbed the “mechanism of failure.” In order to increase shelf life, the mechanism of failure is identified and addressed, then a new mechanism of failure will emerge, ideally at a later date.

For example, if your retain program indicates that you have mold growth year-round in 20% of your yogurt batches at 45 days, the BUB date might be listed as 40 days. By creating “hurdles,” such as changes to ingredients, processing, or the environment, the incidence of mold becomes less prevalent, only affecting 5% of batches at 60 days. However, you may note other changes occurring at 50-55 days and opt to keep the shelf life at 50 days overall. Other degradations are more or less important for each manufacturer but may include:

- Probiotic viability or general thermophilic total plate count

- Flavor changes (post-acidification, decreased diacetyl, light oxidation, fruit prep flavor loss)

- Texture changes (e.g. whey separation)

- Color changes, especially fruit prep

In terms of degradation from unwanted microbiological growth, stopping or slowing the growth of contaminating bacteria, yeast, or mold is the overall goal. Factors that influence microbial growth may be intrinsic to the food (water activity, salt content, pH, presence of antimicrobials or competitive flora) or extrinsic (temperature, oxygen presence, relative humidity, etc).

For better or worse, some dairy products are very narrowly defined, and certain hurdles are impractical. As an example, raw milk has a very short usable period, less than 72 hours for processing. Pasteurized milk typically has a 21-28 day shelf life, but if we try to employ a lower pH to extend shelf life, we suddenly have stopped making fluid milk.

Main take-home: There is seldom one intrinsic or extrinsic factor that can completely preserve a food, but when multiple factors are manipulated to act as “hurdles,” the combined effect is much greater.

Antimicrobials as an Additional Hurdle for Yeast and Mold

Protective Cultures

Overview: One of the biggest areas of interest in the last five years has been natural food protection. The cultures listed below and other similar options help to prevent the growth of yeast and mold through the production of organic acids in addition to the lactic acid produced by your starter culture.

Labeling: A great attribute of protective cultures is that they grow alongside your current starter. Labeling changes are minimized with the use of this type of ingredient. Some products (e.g. plain yogurt: milk, cultures) do not have to change at all. Some manufacturers will include these species in their starter culture listing to be consistent, but others alter their label to something like “cultures including A, B, and C” in order to allow for some flexibility in additional culture usage.

Specific products:

| Family | Culture | Fresh Fermented Application Area |

|---|---|---|

| Danisco HOLDBAC® | YM-XPM | Mild and very mild |

| Danisco HOLDBAC® | YM-C Plus | General use |

| Danisco HOLDBAC® | YM-B Plus | General use |

| Chr Hansen FreshQ® | FreshQ®2 | General use |

The listed products are in a convenient freeze-dried format and currently stocked with no lead time or minimum quantities.

Fermentates

Overview: Cultures also may be used to produce a mixture of antimycotic compounds. The liquid mixture is then dried and powdered and added back to a variety of foods, including dairy products. If your production plant has capability to incorporate dried dairy ingredients, using fermentates is very straightforward. A portion of currently-utilized dairy powder is substituted for the fermentate, usually at 0.1% – 1.5% weight in the finished product.

Labeling: As with any label, trade names are not used. Common declarations include “cultured milk” or “cultured dextrose,” but fermentates are not always individually declared. Seeing as yogurt is inherently “cultured milk,” sometimes it is not obvious that a fermentate is an ingredient of a dairy product. Consult with your local regulators on all labeling changes.

Specific products: A variety are available, but the primary dairy ingredient used in this area is MicroGARD® 100.

Purified Antimicrobials

Alternatively, a purified antimycotic(s) may also be used. In tying in the aforementioned Hurdle Concept, a number of studies investigated the efficacy of combinations of antimycotics, as other precedent shows combined effects being greater than the inhibition of one compound. Examples include natamycin, potassium sorbate, and sodium benzoate.

Note: Some antimicrobials are not permitted in certified-organic foods or by some retailers. All processors should be aware of strict labeling requirements and maximum-allowed usage limits. Included is information on cheese and yogurt application of natamycin.

Main take-home: Added ingredients often do not address the root cause of yeast-and-mold growth, which should independently be investigated. These ingredients may require a label change and do increase the cost of making your products; both factors should be weighed against the potential increases in shelf life.

Cheese: Age is Not But a Number…

As usual, making cheese is like trying to shoot a moving target. During these COVID-19 times, the target seems to disappear and reappear unexpectedly. Slowing cheese aging may be used to bring the target closer and rely less on a perfect trajectory.

In cheese terms of weeks, months, or years of shelf life, we are often looking to lengthen the peak window of optimal ripeness rather than avoiding clearly objectionable defects. Some consumers can appreciate a strong-smelling runny washed rind, but that smaller crowd of consumers may not be large enough to support your normally-spreadable supply of cheese.

In considering your marketing approach, is the product you are selling consistent with what you are marketing? Has your mild cheddar turned medium? Is the cheese already labelled? What if your window of aging for mild cheese went from 1-3 months to 2-5 months?

Temperature

Low means slow. Slower, at least. Cheese is a biological system, with glycolysis, proteolysis, and lipolysis occurring as a result of native or added microflora and enzymes. Temperature is a great extrinsic tool we can use to decrease the rate at which this occurs, especially for vacuum-packaged cheeses.While cooler might be better, freezing is to be avoided, except with a select group of cheeses intended for select applications. See the CDR Resource Technical Bulletin: Strategies to Properly Store or Extend Shelf Life of Cheese for more information.

Anecdotally Speaking…

“Working in procurement, operations and as a grader for a packaging operation for [too] many years, it was common to have periods where cheese sales were slower than anticipated. Being committed to manufacturers for fixed tonnage, it was also common for inventory to increase over desired levels. Brick, muenster, Monterey Jack, and Colby were the most likely to break down beyond prime condition for packaging in retail slices or chunks during these times. The solution was to hold those cheeses in the coldest areas (normally the basement level coolers of multi-storied cold storages) available. I can attest to the practice of holding cheese at temperatures of 32-34°F being effective at keeping product in condition to be packaged with high speed equipment for 4 to 6 weeks past what storage at 40-45°F would have allowed. Fortunately, that was usually enough time for inventory to be back in line, and it was not necessary to see what kind of further extension was possible with that practice.”

— Bill Rufenacht, Dairy Connection Technical Specialist

Practical Considerations

- Will cheese need to be transported and stored at an outside facility?

- Do you have the space available?

- What is your ability to reduce cooler temperatures to the desired level (32-34°F)?

- What is the cost involved in aging cheese? What is the cost of tying up your cash, transport, outside storage, or additional utility cost in operating a storage area at decreased temperature?

- Do you have an established aging program or are you willing and able to detect flavors or textures that will become more pronounced with aging? Is there a possibility of making a less desirable cheese if aging (albeit at a lower temperature)?

- Are you confident with the integrity of packaging materials, vacuum, and seal? Leakers will inevitably mold with age.

Exceptions

- Cave-aged or natural-rinded cheeses can dry out at cooler temperatures without a compensating HVAC system. In general, cooled air is dry, and cooler air is drier. Even with a “smart” air handing unit, fluctuations in relative humidity can change with a major temperature adjustment. Significant rind thickening, lower yield overall, or cheese cracking should likely be avoided instead of trying to cool the cheese further.

- Bloomy-rinded cheeses need to ripen at elevated temperatures in order to promote the correct succession of yeast and mold. Once packaged, if humidity conditions allow, these cheeses may have an extended usable window if stored cooler.

- Raw milk cheeses need to be aged at or above 35°F. It is not completely clear if the aging temperature must be >35°F for the duration of the cheese aging or if only for the first 60 days. Consider natural variations in average cooler temperature and within-cooler variability if lowering aging temperature.

A great resource:

Wisconsin CDR Webinar on Extending Shelf Life: https://www.cdr.wisc.edu/about/coronavirus

Again, every situation is unique, and we encourage you to reach out with your technical and ingredient questions as you navigate the various options for your operation. We’re here to assist, and/or to point you toward additional resources.

Sources

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. GRAS Notices. GRN 517 – Natamycin.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 21 CFR § 172.155. Natamycin.

- Infanger, RC. DuPont-Danisco. American Cheese Society Conference. 2012.

- Leistner L. 1992. Food preservation by combined methods. Food Research International (25) 151-158.

- MacBean RD. 2010. Packaging and the Shelf Life of Yogurt. Food Packaging and Shelf life. Chapter 8. Taylor & Francis Group. Boca Raton.

- Wendorff B; Smukowski M. 2007. Handling Cheese to Maintain Quality. Wisconsin Center for Dairy Research Dairy Pipeline (Vol. 19 Issue 4).

- Wisconsin Center for Dairy Research. 2020. Technical Bulletin: Strategies to Properly Store or Extend Shelf Life of Cheese.

- Wisconsin Center for Dairy Research. April 8, 2020. FAQ Frequently Asked Questions: Strategies to Properly Store of Extend the Shelf life of Cheese.

Recent Blog Posts

-

Featured Product: Natural Calf Rennet

By: Bill Rufenacht | Technical Specialist, Dairy Connection Inc.As you may be aware, we have experie …19th Jun 2024 -

Featured Product: YoMix© ABY-2C Yogurt Culture

By: Bill Rufenacht | Technical Specialist, Dairy Connection Inc.YoMix© ABY-2C is a yogurt …2nd Apr 2024 -

Featured Product: Bioprotective Cultures

By: Bill Rufenacht | Technical Specialist, Dairy Connection Inc.Let’s take a look at bioprotective …15th Feb 2024